- Home

- William Pullar

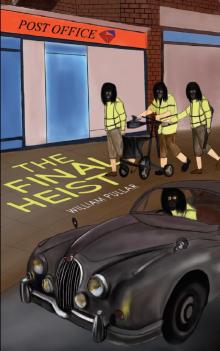

The Final Heist Page 2

The Final Heist Read online

Page 2

Alongside her sat two be-suited men. One seemed to be the spokesperson. “We’re from the council housing department. We represent the manager, Hilary St Claire. She’s on leave.” Short and to the point. Neither smiled.

Carol Smythe took over the conversation, “Well, chaps, this could be a new start for all of you. This is the only place in the south of England, where four furnished flats are currently empty in one building. All of you expressed a desire to be near each other.” She looked at All Four, paused and added, “These two gentlemen are from the council, as you know. They will show you one of the flats.” She banged the table to attract their attention. The men were mesmerised by the ample cleavage on display, thanks to a low-cut blouse.

She banged on the table again, “Anyone at home?” The Colonel coughed and with the other three, looked across the table at the two unsmiling men, aged about forty. One opened the dialogue by stating, “We’ll show you all flat number two. If you say ‘yes’, all four flats are immediately available. They have already nominally been allocated to you.” No one had accounted for a situation if they declined the offer.

Reg sat down on a dining-room-style chair. Holding the handles of his trolley, he asked, “Is there one on the ground floor?”

No one smiled. “Yes, there is,” answered one of the officials.

Reg Crowther was a sad case. The one-time security van and bank robber who began his criminal activities, aged thirty-two, after being jailed for his sixth-drink drinking offence and driving whilst disqualified. The stories of derring-do from other prisoners appealed to his sense of adventure. So, he began his ‘career’ as an armed robber.

He had spent most of the past forty years as ‘guest’ of the prison service after his childless marriage broke up. In addition to joining the criminal underworld, he spent his non-custodial time in various pubs and bars. When locked up in the confines and restrictions of prison life, he relied on the comfort and pleasure of smuggled in whisky, brandy or prison-produced hooch.

The effects of too much alcohol created a condition known as Central Pontine Myelinolysis, also known as Osmotic Demyelination. The protective cover of the spinal cord had eroded, and his vocal chords damaged, leaving him with poor balance and a reliance on walking aids, such as a four-wheel ‘walker’, a zimmer frame or walking sticks. He now spoke in a whisper. His vocal cords had been damaged, leaving him struggling to talk and destroying his once stentorian voice.

He’d been diagnosed at the beginning of his last jail term. Like his three friends, he preferred the discipline of prison life. The prison authorities decided he was too much bother to cope with his walking problems and his four-wheel trolley. They wouldn’t allow walking sticks as they could be used as weapons.

This restricted his ability to move around.

Few knew that in his heyday, he was aggressive, belligerent and a seasoned ‘blagger’ of banks, post offices and security vans. His usual persuader was a Purdey double-barrel sawn off shotgun.

The four then inspected flat number two with the Colonel, expressing his surprise at how well-furnished it was and so clean and tidy. The two council men smiled for the first time, taking the Colonel’s praise as a compliment. “They’re all the same,” said one, who spoke for the first time.

They returned to a corner of the day-lounge, where they met the diminutive warden of both complexes, Mary Murphy, who had only held the post for two weeks when the four arrived. She greeted all with what could only be described as firm handshakes. “Welcome to the Retreat,” she declared, with well-rehearsed enthusiasm.

Little did the four realise this podgy little woman, with a permanent smile, was to become one of the menaces of their lives. Just to add to their social problems, she was married to the Reverend Bernard Murphy, the recently appointed vicar of the nearby Church of England Church, St Jaspers, often referred to by non-Christian wags as St Jokers.

Like his wife, he was height-challenged. His aim was to increase the number of Sunday worshippers from the three regulars, sometimes five on a Sunday. Various recruitment schemes had all failed. Now, he had a new plan, a cunning plan. A phrase he admitted he’d borrowed from the character, Baldrick, in the TV series, Blackadder. All he needed was the right team to help him.

The Colonel took an instant dislike to Mary Murphy. His dislike the intensified, mainly because he had become unused to any woman dictating what he should or shouldn’t do, and when. This dislike grew even more when he discovered this strange woman once held the title of Champion Lady Boxer and was once part of a touring All Ladies Boxing Team. He had a dislike of pugilistic women.

She’d met the man she called ‘the love of her life’ when he led a demonstration against female pugilism at a Birmingham hall, staging an all-ladies boxing tournament.

Her plan was to bring all the residents’, social welfare types and the private ones, into a well-organised daily routine she would manage, a plan that was to be well-meaning in concept but a disaster to implement. She now had the added challenge of the four. She hid one secret from her gentle and kindly clerical spouse. Twice a week, she secretly visited a Brighton gymnasium, hoping to reduce the width and weight she’d accumulated since marriage, and more so of late.

Carol Smythe pulled out of her briefcase a bundle of documents, and said, “These, gentlemen, are your contracts. I suggest you read them carefully before signing.” At this point, Mary Murphy, and the two council men, moved to another set of lounge chairs and a table at the opposite end of the room and started another meeting.

Mizz Smythe, as she liked to be addressed, as if to re-enforce her unmarried status, continued her welcoming chat, “Now, chaps, you should know, unlike other arrears, we work closely with the prison people, the council and residential homes where we place chaps, and sometimes ladies, to help their rehabilitation into the outside world.” She smiled at All Four.

They each forced a smile in return. “Yeh, these contracts look good to me,” the Colonel announced. After a short pause, Reg and Jock nodded their approval. Lenny continued perusing the document. The fact he could hardly read went unnoticed. He trusted the Colonel. He handed the document over. Carol Smythe added forcefully, “You must realise that we do not allow pets.”

Reg inquired, “What not even caged rats or birds, not even goldfish?”

“You’ll have to make an application to the management board through the warden. Dogs and cats are certainly out.” Her mobile phone trilled a strange tune. She said, “Forgive me, chaps. I need to take this call.” She answered the mobile phone, stood up and had a conversation out of earshot.

Lenny suddenly said, “God, that woman who wuz in the Carry On Films is slimmer than her, yer know. What’s her name? Hetty Jakes.”

Jock answered in understandable English, “Was y’ mean? Her name was Hattie Jacques.”

“Yeh, her, that’s who I mean,” Lenny confirmed.

Lenny had a perchance of likening anyone to a TV or movie star, a trait that, sometimes, caused acute embarrassment or laughter.

Carol returned to the group and from her case, she took out four A4 brown envelopes. Opening one, she spread the contents in front of them and using her ballpoint pen as an aid to her demonstrating she said, "Now, we have a local arrangement with these stores. The vouchers are for Cooper’s bedding store in town; the other is for Tesco’s. You need to know the ones that add up four hundred pounds for bedding and suchlike, the other four are for one hundred to enable you to buy groceries etcetera.

“Now, you need to understand you don’t get change if you don’t meet the face value of each voucher.” My advice is that you spend as much as you can on each voucher, as you won’t get any cashback. Now, on another front, you need to know your pension’s and other benefits will still be paid into your respective bank accounts. My staff will help you notify the department of works and pensions and the banks about your change of address," she smiled again and stood up. “That’s all for now. I’ll give you a lift into town.”

Little did Carol Smythe realise these four would give the biggest challenge of her career, not that they would want to challenge this rather large lady. Her liking for locally produced ‘veg’ would lead to acute embarrassment for the probation service.

Mary Murphy stood up and walked over to them, followed by the two council workers. She looked up at the four. They looked down at the height-challenged dumpy lady. “Welcome to our happy home,” she said as she shook their hands.

The council men smiled and simply said, “Welcome.” It was now 1:30. As they were leaving, they met a business-like lady aged about forty, dressed in light green trousers and T-shirt with the logo: Who Care. A wag had scrawled an S at the end of Care with a felt-tip pen.

Mary Murphy introduced Liz Forgan, the manager of the care company, whose staff attended the daily needs of some residents. Reg was quick to say, “That’s just what I need, daily help especially at night.” The Colonel interrupted and said, “We’re in a bit of a hurry right now. Can we meet you in the morning?” He added and looked at the others, who all nodded. “OK, we’ll see you in the morning at ten.”

“Yes, yes,” the care company manager replied. As they were about to leave, Carol Smythe waddled towards a rear door leading to the garden and said, “I’ll only be a few minutes. I need to collect some veg. She returned a few minutes later with a plastic carrier bag, saying:”OK, I’ve got what I want. Let’s go."

As the Colonel opened the door to leave, they were confronted by a formidable-looking lady in her seventies, in a distinctive English cut-glass accent and dressed in a green country-style, tweed-patterned, two-piece suit with the skirt’s hem finishing just below the knees and a raffia hat donned in a rakish manner with the right side almost obscuring her eye and the left side pinned up. A Paisley-patterned scarf was held in place by a silver broach, covering her throat. She asked with an ingratiating smile, “Hello, gentlemen. You’ve moved in, yes?”

The Colonel responded, “Maybe. Why do you want to know?”

Jock added to the greetings with, “Ciamar a tha thu, hen?”

The lady winced, taken aback by this strange language uttered by this tall, well-built, ginger-haired man.

“Oh, you’re foreign.”

Jock smiled at the look on her face.

“Nay Lassie, ann an Ecosse kalik, ye ken.” He smiled at her.

With a bewildered look on her face, she took another step back. His three comrades stayed quiet, enjoying the ‘conversation’. Two of them, like the country-style woman, hadn’t a clue what had been said. The gang all knew from old that when Jock was sober, few people had a real inkling of what he was saying. He always tried to have a quarter bottle of whisky about his person. A ‘wee dram or two’ had a curious effect of improving his verbal communication skills.

Lenny was about to speak when a look from the Colonel stopped him.

“I’m Martha Samuels. I run the residents’ committee.”

“Congratulations, madam, it suits you.” The Colonel addressed her without a trace of a smile.

Pulling herself up to her full height, she clasped her hands across her stomach, puffed out her ample chest and in a rather grand response, continued, “Do you know who I am?”

The Colonel, in a rare example of humour, replied. “Gawd, that’s awful, not knowing who you are. I can’t help you.”

With a loud, verbal ‘umphh’, she turned and walked out. No one could speculate where this encounter would lead.

One of the two council men commented, “What a ghastly woman. I’ve never seen anyone silence her before. You’re a very brave man.”

Mary Murphy covered her mouth and let out a muffled giggle.

One of the council officials turned to Jock and quietly asked, “What did you say to her?”

Lenny interrupted, demonstrating a rare skill he’d acquired, “He told her he was Scottish Gaelic. I’d managed to understand a good amount of the lingo after spending some time in and around Glasgow and working with him.”

“Ask a silly question,” the council man muttered under his breath.

Lenny turned and stood with his back to the others, then very quietly asked Mary Murphy, “What was that rumpus when we arrived, the ambulance, the old lady and the cops?”

“Well,” she replied, “I don’t know why she did it. That was Jessica Creswell from number twelve. She’s a retired teacher. Why she battered our in-house doc with her walking stick, I’m not clear.”

Lenny nodded and followed the others to Carol Smythe’s people-carrier for the ride into town.

Two hours later, All Four had loaded themselves with new bedding and towelling. They, each, managed to spend between £190 and £198 at Coopers. At Tesco’s, the girls at the check-outs smiled and made them welcome. They, each, managed to spend the whole of their £100.

Waiting for their taxi, they sat in a harbour side café and ordered tea. The Colonel commented, “That warden woman is very odd. As for that woman who says she chairs the committee, she’s dangerous. Can’t imagine any man coping with that harridan. All that aside, we’ve got nowhere else to go. If we throw in the towel, then it’s back to the nick, toot suit.”

Lenny was the first to respond, “Cor, I bet she was a looker when she was younger.” No one replied. There was a couple of minutes silence then Reg asked Lenny as Jock replenished his whisky glass at the bar, “Do you really understand Jock when he’s sober?”

“Oh, yeh, we’ve spent time in a couple of nicks and the governors used to ask me to interpret. Do you know? The cops used to get him tanked up on whisky, so they could understand his explanations of why he was nabbed at the scene. Caught in the act, you might say. It was so comical, a whisky-assisted confessional.”

Lenny chuckled at his own attempt, at what he thought was humour. “I’ve a good mind to apply to have a budgie; that’ll fool ’em.”

Jock had now downed his third large neat Glenmorangie. He nodded in agreement and said in a more understandable language, “Ay, sleeked, tattie heads, didn’t tak to the bint. I said hello, then telt her I wuz Scottish Gaelic. It’s pronounced ka-lic. It usually confuses.” He held an empty glass in his outstretched hand, in the hope someone would re-charge it.

Lenny quietly said, “He said cops were sly potato-heads. He doesn’t like that Martha woman, and he spoke to her in Gaelic. That’s it.”

“Ay, she’s a numptie English bint,” Jock said quietly, standing up and heading for the bar and a refill.

“Oh, you fancy her, then?” The Colonel called after Jock, who blew a raspberry and replied with a loud, snorting noise.

After a short period, Lenny leaned across the table and announced conspiratorially, “You know who she reminds of?” “No,” replied Reg Crowther.

“That woman in the TV series; you know the one who thinks she’s posh and bullies her husband. What’s her named? Her real name is Bucket. She calls herself after a bunch of flowers, Bouquet. She looks, speaks and acts just like her. Can’t say I’ll take to Martha Samuels. As fer that probation woman, she could give us grief—”

Lenny interrupted, “What I’d like to know is why was that woman wantin’ to be arrested, and who was in the ambulance? I think we should know.” He thumped the table.

No one responded.

Chapter 2

LATE in the afternoon, all had taken up residence in separate furnished flats in the Retreat Residential Complex. It mainly housed needy pensioners. Part of the complex also housed wealthy private individuals, who generally ignored their benefit supported neighbours. The flats were designed for elderly residents, some still able, with daily visits from professional carers to look after themselves.

There average age was eighty-two and a mixture of opinionated, cantankerous, just plain, awkward and reclusive individuals whose antics caused a mixture of amusement and head-

shaking from council officials, carers and others. Some were from the Essex and East London Borders. Others were from the rural areas of Kent, Sussex and Surrey – a strange cultural mix.

As the four were settling in, Police Sergeant Craig Wallace at Crabby’s Decrepit old police station, read a copy of an email sent to HQ from the prison service regarding four old men, who’d been released and were about to take up tenancies in flats at a residential home in the town. The e-mail stated that All Four were no longer a threat to society. To Sergeant Wallace, one name stood out, Guy Granger, as the letter said he was also known as the Colonel. The sergeant telephoned his father, a retired Metropolitan Police Detective Chief Superintend. “Dad, you’ll never believe whose been deposited on my patch.”

“You’ll tell me, no doubt,” the retired, old copper replied. “Go on. Shock me. I need a laugh.”

“Guy Granger, you know the old lag, who calls himself Colonel. He’s been released from nick with three of his pals into a residential home in town.”

The retired, old DCI replied, “Gawd, they must all of eighty each. Let’s see if I’m right about the others. Reg Crowther, he used a sawn-off shotgun. A hard man if ever there was. Then, there used to be a Lenny. Let me think.” After a pause, he continued, "Ah, Lenny Smith, big man like Reggie. He liked his shotguns. Every time we nicked him, he was in bed with a different woman. Gawd, he didn’t half put it around. Don’t know what they saw in him. Big, ugly and as thick as two short planks.

"Then, there was the Scotsman, Jock Mackenzie. Now he was weird. He used to talk a strange mixture of normal Glaswegian slang, mucked-up form of English and that Scottish language; what’s it called? Oh! Yes, Gaelic.

“You know, whenever we nicked him, we bought a half bottle of whisky, so we could understand him. As he drank more whisky, the clearer his confessions became. Weird it was! He often asked for an interpreter, who didn’t understand a word he said. The situation often caused a few giggles in court.”

The Final Heist

The Final Heist